Members

1 Male

Origin

---

---

Genre

---

Style

---

Mood

---

Born

1 Male

Origin

Genre

---

Style

---

Mood

---

Born

1947

Active 1947 to Present...

Cutout

Alternate Name

Wifredo José Chirino Rodríguez

4 users

4 users

4 users

4 users

4 users

La jinetera |  Medias negras |  Yellow Submarine |

Artist Biography

Available in:

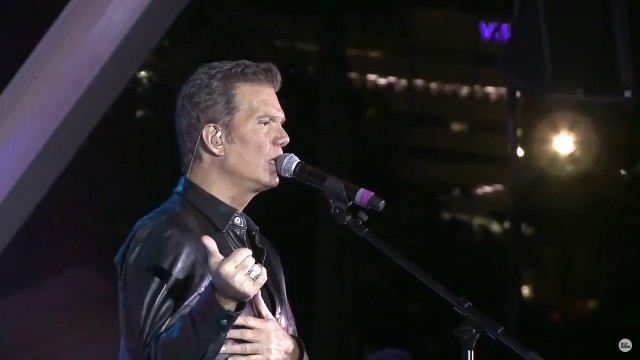

Combining the musical traditions of Cuba with American rock and jazz, Cuba-born and South Florida-based vocalist and bandleader Willie Chirino helped to create the "Miami Sound" of Salsa music. The composer of more than one hundred songs, Chirino's material has been covered by a lengthy list of artists including Raphael, Ricardo Montaner, Rocio Jurado, Celia Cruz, Oscar D'Leon, Angela Carrasco, Jorge Muniz and Nydia Caro. Chirino's song, "Soy," has been recorded by more than sixty artists including The Gypsy Kings, whose interpretation sold more than four million copies. Chirino also composed and performed the theme songs for Spanish-language television soap operas, "La Zulianita" and "Pobre Diabla."

Chirino has received numerous awards throughout his career. He was named "King" of Miami's Calle Ocho Festival in 1993. Two years later, a section of NW 17th Avenue in Miami was christened "Willie Chirino Way". Chirino received a UNICEF award for his work for children via the Willie Chirino Foundation.

When the teenager Willy Chirino left Cuba, one of the 14,000 children and young people who arrived in Miami in the early 1960s through Operation Pedro Pan, his head was full of rhythms and his soul was filled with music. He would be a musician, even though his father, a prosecutor in the Pinar del Rio court, expected his son to study law.

Willy Chirino became an excellent musician. He sang, composed, conducted his orchestra, recorded. Every day he won over more and more audiences.

Chirino had "angel." Cubans, especially those in Miami, considered him one of them; Willy was a simple, approachable boy. One of those who "do not stop"; one of the few for whom success "does not go to their heads."

They applauded him; they loved him. He had even married another popular Cuban singer, also a "Pedro Pan girl": Lisette Alvarez. Then in 1990, when communism collapsed in Europe and everyone believed that in Cuba, at last!, the sun would rise again, Chirino composed "Nuestro Dia (ya viene llegar)" (Our Day (It's Coming Soon) which brought pure emotion to the driest Cuban eyes. And the entire exile, from Miami to Alaska, from New York to the farthest corner of the universe, there are Cubans even on the moon, "adored" that "Cuban boy." And at the same time they laughed at "Mister, don't touch the banana." Music, more than ever, filled Willy Chirino's life.

The Change

But the signs seem to indicate that a change has occurred in Willy Chirino's life. For some, subtle; for others, evident. Who would have thought that in the midst of that high tide of professional success, there was a corner in the soul of the salsa singer that remained "untouched" by rhythm and melody?

"Music is very important to me, but there is a place in the soul that is not filled with music; a place that music cannot reach," says Chirino. "That place is only filled by the satisfaction derived from helping someone else. What you feel when you help a child, a family, has no equivalent." Perhaps Chirino is practically discovering this now, less than three years ago. He always had a reputation for being "a good boy," never reluctant to lend a hand. Close to the Catholic Church, he is grateful to Operation Pedro Pan and, above all, to his admired Monsignor Bryan Walsh, soul and life of the Operation, an important chapter in the history of Cuba and the exile.

But the Willy Chirino Foundation is much more than occasionally reaching out a hand in need: it is a dedication to service.

"The true purpose, the mission of the human being, is to serve his fellow men," says Chrino, convinced and convincing. "Monsignor Boza Mas Vidal once said that he who does not live to serve is not fit to live." However, the original idea did not actually contemplate such total dedication. At first, the plan was related only to art. The idea had perhaps been born from a conversation with Armando Lopez-Salamo, a journalist who arrived from Cuba in the early 90s, currently editor of the magazine Empresa, who at that time was working with Chirino on issues related to music: the newly arrived Cuban artists and writers had no support.

Willy Chirino Foundation

At the beginning of 1994, Chirino began the steps to help Cuban artists who were arriving in the United States to have a new beginning. "The idea was to provide writers, composers, singers, painters, playwrights, who were joining the democracy and who did not have a vehicle to express themselves, a platform to exhibit their art," he recalls. But soon rafters began to leave Cuba in large numbers, and to be detained at the Guantanamo naval base beginning in August.

"We had to change course. We had to help these people, above all show them solidarity, tell them that they were not alone," says Chirino. On the walls of the offices of the Willy Chirino Foundation hang large photographs of the "salsero" greeting the rafters in Guantanamo, talking to them, singing to them. On one of the walls, a pair of rudimentary oars that one of them gave him as a souvenir of his odyssey at sea, has been adorned with white, red and blue fabrics.

The rafters of Guantanamo, especially the children, left their mark on the artist. Something began to reach that corner of Chirino's soul that music had not reached. Donations to rafters in Guantanamo, Bahamas, Dominican Republic, a rafter excursion to Disney World, scholarships to study, opportunities for families to celebrate Christmas, Thanksgiving Day, clothing, food, problem solving for Cubans in Pachacamac, Peru, where more than a hundred families of those who sought asylum in the Peruvian Embassy in Havana in 1980 still live.

The works of the Willy Chirino Foundation are practically innumerable. The tragedy of the Cubans is wide and has many branches. The foundation discovered one of the most dramatic episodes: the Cubans in third countries.

"We Cubans have boasted, and rightly so, about the Cuban success. It really has been like that: we are hard-working, productive, and we have reached an extraordinary economic level both in South Florida and elsewhere. But no one talks about the thousands of other Cubans who are scattered around the world, in misery, looking for food in garbage cans, about the elderly without medical attention, about the children who cannot go to school. Nobody helps them, neither the governments, nor public or private entities."

Lawyers who work voluntarily with the Willy Chirino Foundation try to help them by offering legal advice. Some may be able to enter the United States, which is what everyone is after; others will never succeed because they have no relatives here.

But the real tragedy, Chirino points out, is that of those in a "legal limbo," those who entered a country without authorization and are not allowed to work, nor do their children have the right to attend school. Even more terrible are those who have arrived in countries that have deportation agreements with Cuba. They live in hiding because they are persecuted. If they are caught, they are deported to Cuba.

These countries include Jamaica, the Bahamas, and Sweden, the latter being the country where many Cubans who were in countries of the Soviet bloc when communism collapsed there entered.

"Cubans in these nations live hidden in basements. They are persecuted in the style of the Gestapo during World War II. If they are captured, they are immediately deported to Cuba. Some have told us that they prefer to die than return to Cuba," says Chirino. The cases are referred to the Willy Chirino Foundation by family members or friends. A few months ago, Chirino met with the President of the Dominican Republic, Lionel Fernandez, and more recently, on February 6, the executive director of the foundation, Gisela Hidalgo, did so. They arrange visas for these Cubans, not only there, but in other countries such as Venezuela, Peru and Ecuador.

"We want to ensure that these Cubans can legally enter a country, have a work permit and lead a normal life. That is our basic function at the moment," says Chirino.

The foundation's work continues to be innumerable... and expensive. To bring a child to Miami who was suffering from a strange illness in Cuba that prevented him from breathing, it was necessary to send a plane to Cuba. He was treated at the Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami.

"The first time in 20 years that something like that was achieved," says Chirino. The foundation is building a school in the Dominican Republic, sent a large donation to Colombia when a fatal landslide occurred recently; last December, four thousand toys were sent to Nicaragua.

And a second foundation is already in the works, the Willy Chirino Inner City Foundation, to deal with community issues. "There are so many tragedies and tragedies. At the end of last year, a Cuban woman who had been here for only six months brought her eight-year-old daughter from Cuba. Three weeks later, on December 24, she tried to poison her. The woman said she was depressed because she couldn't buy the girl a toy for Christmas."

Chirino visited the little girl in the shelter where she had been placed; it was for African-American children. No one spoke Spanish there. Another child brought from Cuba by his father wants to return to Cuba: the father is constantly drunk and beats him.

"So it breaks your heart to see so much sadness," Chirino emphasizes. The Willy Chirino Foundation has held two galas in the last two years. The tables were sold for $1,500, $2,500, $5,000 and up to $15,000. Chirino's orchestra and artist friends performed for free. Many personalities from television and the business world attended. Between the two, $385,000 was raised. A third gala will be held in New Jersey in May of this year.

"We have companies like Chevrolet that have donated $75,000 to us each year, and sponsorship from other companies and hospitals that have made considerable contributions," Chirino says.

The owners of an elegant building in Miami Beach are providing the premises for the foundation's offices free of charge; others have provided a warehouse for donations of food and clothing.

"A lot of people help. We have a lot of volunteers. Only the two secretaries and the executive director get paid here, because they devote all their time to the foundation and have families to look after. All the rest of us work for free," he explains.

Willy Chirino is filling that "corner of the soul that music doesn't reach." "Those who discover that the mission of human beings is to serve and fulfill it, fulfill their spiritual life and get closer to God. Serving puts one in contact with God, not at the level of prayers or visiting temples, but by acting in the way that I believe He, in His greatness, wants us to act," said the musician.

Chirino says he sees God in a "somewhat different" way. He does not see an "arrogant" God who needs to be "flattered," but rather a God who judges us and approves of us for the way we treat other beings: parents, siblings, children, friends, animals, and the environment. In other words, God judges us for the love we are capable of giving.

He also thinks that "everything in life has a purpose" devised by God and that everything is ultimately for the benefit of humanity, even if it may not seem so at the moment.

Wide Thumb

Clearart

Fanart

Banner

User Comments

No comments yet..

No comments yet..