Cover NOT yet available in

Join up for 4K upload/download access

Your Rating (Click a star below)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

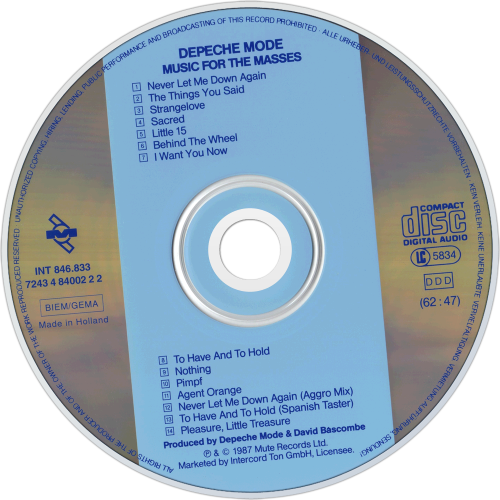

Track List

01) Never Let Me Down Again

02) The Things You Said

03) Strangelove

04) Sacred

05) Little 15

06) Behind the Wheel

07) I Want You Now

08) To Have and to Hold

09) Nothing

10) Pimpf

01) Never Let Me Down Again

02) The Things You Said

03) Strangelove

04) Sacred

05) Little 15

06) Behind the Wheel

07) I Want You Now

08) To Have and to Hold

09) Nothing

10) Pimpf

4:48

4:02

4:54

4:49

4:18

5:18

3:44

2:51

4:18

4:55

Data Complete 80%

Total Rating

Total Rating

![]() (3 users)

(3 users)

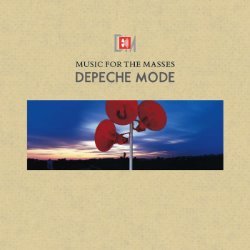

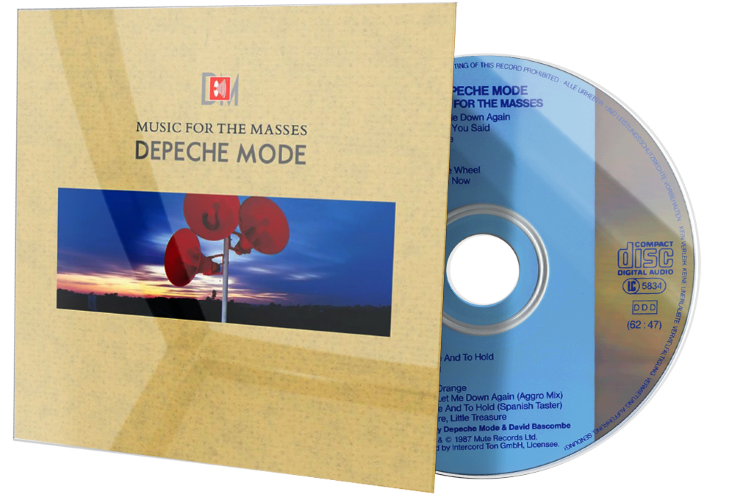

Back Cover

CD Art

3D Case

3D Thumb

3D Flat

3D Face

3D Spine

First Released

![]() 1987

1987

![]() Synthpop

Synthpop

![]() Moody

Moody

![]() Rock/Pop

Rock/Pop

![]() ---

---

![]() Medium

Medium

![]() Album

Album

![]() 4,200,000 copies

4,200,000 copies

Album Description

Available in:

La musique pour les masses est le sixième album studio par Depeche Mode. Il a été publié par Mute Records le 28 septembre 1987 et a été soutenu par la Music for the Masses Tour.

Les membres du groupe Andy Fletcher et Martin Gore ont tous deux expliqué que le titre de l'album avait été conçu comme une blague. Fletcher a déclaré: "Le titre est ... un peu ironique, vraiment. Tout le monde nous dit que nous devrions faire plus de musique commerciale, donc c'est la raison pour laquelle nous avons choisi ce titre." Selon Gore, le titre "était une blague sur l'incommercialité. C'était tout sauf de la musique pour les masses!"

User Album Review

These reissues-- of arguably the three most beloved records in Depeche Mode’s catalog-- come in a slightly baffling format. Each package contains one CD, for the remastered album, and one DVD, featuring a pointless 5.1 Surround Sound mix, a small handful of bonus tracks (playable only via DVD), and a 20-minute talking-head documentary on the making of the album and the corresponding period in the band’s career. The decision to include those documentaries seems telling, and it seems like a struggle to get at the one thing that reissues-- no matter how many B-sides or demos they throw at you-- can rarely capture: How and why a band in question seemed so very cool at the time.

That turns out to be a big issue with Depeche Mode. These days, the sound of their older records seems less like a revelation and more like a given: The band’s vibe has evaporated out into America to the point where you can spot it in anything you want, whether it’s Linkin Park, Marilyn Manson, or Britney Spears. (Rather incredible, for a British group.) These days, their carefully crafted look has them resembling a failed Hungarian metal band and their reputation is just that of a big, respectable, slightly drama-queeny pop act-- idiosyncratic, maybe, but hardly that unusual. New listeners cannot expect to hear these albums quite the way their fans did at the time.

What’s funny is how that affects each of these records differently. With 1990’s Violator, the band’s pop-crossover classic, it makes hardly any difference at all; the way most people think about and imagine Depeche Mode was built largely on this record. Interview subjects in the documentary have much to say about how “perfect” the album is, how neatly and naturally it matches the sounds and synths of “progressive technopop” with the kind of grand songwriting that can play to massive stadiums. And they’re right. Like any good crossover, this record needs no particular context to appreciate, and listening back through, one gets a sense of why: The battle they’re winning here, of giving electronic music the human feel of teenage anthems and power ballads, is the same one still being fought by any number of Germans; it’s not constrained by time. The dark and slinky soul of the record-- the sex or drama-queen poses, the mix of domineering threats and extreme tenderness-- don’t hurt either.

But in carrying its context with it-- and in being somewhat critical to today’s pop-- Violator just stands as a moving, solid, record, a classic for the archives of popular music; it doesn’t so much carry a lot of the things that made Depeche Mode feel so much themselves. With 1987’s Music for the Masses, that stuff is all there-- which makes the music both harder to “get,” from today’s perspective, and also more interesting. The Depeche Mode of this album is the one that brought together a rabid audience of trendy coastal kids and middle-American teens who got beat up over stuff like this-- all of whom saw them not only as the peak of style, but as something positively revelatory, something speaking only to them (even in a crowded stadium), something alien and cool, disorientingly kinky, and entrancingly strange. For many, this was probably one of the first dance-pop acts they’d heard that didn’t seem to be entirely about being cool and having a good time; their music had been dark, clattery, and full of S&M hints and blasphemy, and on this record it reached a level of Baroque pseudo-classical grandness (see depressed-teenager shout-out “Little Fifteen”) that lived up to those kids’ inflated visions of the group.

At the same time, though, this Depeche Mode could be fun, even in its minor keys: The go-to radio pick for this album was the version of “Behind the Wheel” that segued into a cover of “Route 66”. And it’s somewhere around that fact that we might recognize how far we are from the mainstream “alternative” audience of the late-80s, a scene we see in passing between the chatter of the documentary. Anyone looking to understand that context, or just infatuated by the guy in the front row of Depeche Mode’s Rose Bowl concert wearing a Fishbone t-shirt, would do well to look to Depeche Mode 101, D.A. Pennebaker’s tour film-- which, in a canny pre-"Real World" move, spends time following a group of fans who’ve won a chance to follow the band on tour.

With the band’s 1981 debut, the increasingly adorable Speak & Spell, our distance from the original context actually makes things better. Of course, this is not the Depeche Mode we know: The songs on this album were written by Vince Clarke, who would shortly after leave the group and find fame with Yaz and Erasure. And these, of course, are the early days of synth-pop: These songs are building-block simple, bleepy and discoid, and the band sounds as gawky and adolescent as Dave Gahan looked. There’s something terrific in hearing this from a distance, not as stylish futurism (not anymore) but as the happy noises of teenagers who believed it to be stylish futurism-- and with a charming earnestness. “Happy” because of, well, Vince Clarke, whose work with Erasure is a testament to both his love of joyous disco-pop and his ability to pack it full to bursting with emotion. The best tracks here (like the Kraftwerk-y “New Life” and the dancefloor standard “Just Can’t Get Enough”) are classics, and even the lesser ones-- packed as they are with hooks and verve-- can charm you giddy, in the same way it can charm you giddy to see Dave Gahan prancing around in a bow tie on "Top of the Pops" in the documentary: He looks so young! And shy! And they haven’t even started dressing like leather men yet!

What’s funny is that these three records, despite being the obvious standouts for reissue, are some of the most vexed by this whole issue of context and aging. Violator can sound like a solid but not particularly interesting pop record; Music for the Masses seems to be reveling in an audience that’s less comprehensible now; and Speak & Spell is a lovely "historical" gem. Here’s hoping Rhino’s reissue series will be able to make its way further down into the catalog, to those records that aren’t so weirdly situated-- first-rate synth-pop like the songs on Construction Time Again and Some Great Reward, the ones that first developed that American cult around something that didn’t need much social explanation, and probably still doesn’t.

SOURCE: https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/11881-speak-spell-music-for-the-masses-violator/

External Album Reviews

None...

User Comments

Available in:

La musique pour les masses est le sixième album studio par Depeche Mode. Il a été publié par Mute Records le 28 septembre 1987 et a été soutenu par la Music for the Masses Tour.

Les membres du groupe Andy Fletcher et Martin Gore ont tous deux expliqué que le titre de l'album avait été conçu comme une blague. Fletcher a déclaré: "Le titre est ... un peu ironique, vraiment. Tout le monde nous dit que nous devrions faire plus de musique commerciale, donc c'est la raison pour laquelle nous avons choisi ce titre." Selon Gore, le titre "était une blague sur l'incommercialité. C'était tout sauf de la musique pour les masses!"

User Album Review

These reissues-- of arguably the three most beloved records in Depeche Mode’s catalog-- come in a slightly baffling format. Each package contains one CD, for the remastered album, and one DVD, featuring a pointless 5.1 Surround Sound mix, a small handful of bonus tracks (playable only via DVD), and a 20-minute talking-head documentary on the making of the album and the corresponding period in the band’s career. The decision to include those documentaries seems telling, and it seems like a struggle to get at the one thing that reissues-- no matter how many B-sides or demos they throw at you-- can rarely capture: How and why a band in question seemed so very cool at the time.

That turns out to be a big issue with Depeche Mode. These days, the sound of their older records seems less like a revelation and more like a given: The band’s vibe has evaporated out into America to the point where you can spot it in anything you want, whether it’s Linkin Park, Marilyn Manson, or Britney Spears. (Rather incredible, for a British group.) These days, their carefully crafted look has them resembling a failed Hungarian metal band and their reputation is just that of a big, respectable, slightly drama-queeny pop act-- idiosyncratic, maybe, but hardly that unusual. New listeners cannot expect to hear these albums quite the way their fans did at the time.

What’s funny is how that affects each of these records differently. With 1990’s Violator, the band’s pop-crossover classic, it makes hardly any difference at all; the way most people think about and imagine Depeche Mode was built largely on this record. Interview subjects in the documentary have much to say about how “perfect” the album is, how neatly and naturally it matches the sounds and synths of “progressive technopop” with the kind of grand songwriting that can play to massive stadiums. And they’re right. Like any good crossover, this record needs no particular context to appreciate, and listening back through, one gets a sense of why: The battle they’re winning here, of giving electronic music the human feel of teenage anthems and power ballads, is the same one still being fought by any number of Germans; it’s not constrained by time. The dark and slinky soul of the record-- the sex or drama-queen poses, the mix of domineering threats and extreme tenderness-- don’t hurt either.

But in carrying its context with it-- and in being somewhat critical to today’s pop-- Violator just stands as a moving, solid, record, a classic for the archives of popular music; it doesn’t so much carry a lot of the things that made Depeche Mode feel so much themselves. With 1987’s Music for the Masses, that stuff is all there-- which makes the music both harder to “get,” from today’s perspective, and also more interesting. The Depeche Mode of this album is the one that brought together a rabid audience of trendy coastal kids and middle-American teens who got beat up over stuff like this-- all of whom saw them not only as the peak of style, but as something positively revelatory, something speaking only to them (even in a crowded stadium), something alien and cool, disorientingly kinky, and entrancingly strange. For many, this was probably one of the first dance-pop acts they’d heard that didn’t seem to be entirely about being cool and having a good time; their music had been dark, clattery, and full of S&M hints and blasphemy, and on this record it reached a level of Baroque pseudo-classical grandness (see depressed-teenager shout-out “Little Fifteen”) that lived up to those kids’ inflated visions of the group.

At the same time, though, this Depeche Mode could be fun, even in its minor keys: The go-to radio pick for this album was the version of “Behind the Wheel” that segued into a cover of “Route 66”. And it’s somewhere around that fact that we might recognize how far we are from the mainstream “alternative” audience of the late-80s, a scene we see in passing between the chatter of the documentary. Anyone looking to understand that context, or just infatuated by the guy in the front row of Depeche Mode’s Rose Bowl concert wearing a Fishbone t-shirt, would do well to look to Depeche Mode 101, D.A. Pennebaker’s tour film-- which, in a canny pre-"Real World" move, spends time following a group of fans who’ve won a chance to follow the band on tour.

With the band’s 1981 debut, the increasingly adorable Speak & Spell, our distance from the original context actually makes things better. Of course, this is not the Depeche Mode we know: The songs on this album were written by Vince Clarke, who would shortly after leave the group and find fame with Yaz and Erasure. And these, of course, are the early days of synth-pop: These songs are building-block simple, bleepy and discoid, and the band sounds as gawky and adolescent as Dave Gahan looked. There’s something terrific in hearing this from a distance, not as stylish futurism (not anymore) but as the happy noises of teenagers who believed it to be stylish futurism-- and with a charming earnestness. “Happy” because of, well, Vince Clarke, whose work with Erasure is a testament to both his love of joyous disco-pop and his ability to pack it full to bursting with emotion. The best tracks here (like the Kraftwerk-y “New Life” and the dancefloor standard “Just Can’t Get Enough”) are classics, and even the lesser ones-- packed as they are with hooks and verve-- can charm you giddy, in the same way it can charm you giddy to see Dave Gahan prancing around in a bow tie on "Top of the Pops" in the documentary: He looks so young! And shy! And they haven’t even started dressing like leather men yet!

What’s funny is that these three records, despite being the obvious standouts for reissue, are some of the most vexed by this whole issue of context and aging. Violator can sound like a solid but not particularly interesting pop record; Music for the Masses seems to be reveling in an audience that’s less comprehensible now; and Speak & Spell is a lovely "historical" gem. Here’s hoping Rhino’s reissue series will be able to make its way further down into the catalog, to those records that aren’t so weirdly situated-- first-rate synth-pop like the songs on Construction Time Again and Some Great Reward, the ones that first developed that American cult around something that didn’t need much social explanation, and probably still doesn’t.

SOURCE: https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/11881-speak-spell-music-for-the-masses-violator/

External Album Reviews

None...

User Comments

No comments yet...