Cover NOT yet available in

Join up for 4K upload/download access

Your Rating (Click a star below)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Track List

01) 4

02) Cornish Acid

03) Peek 824545201

04) Fingerbib

05) Carn Marth

06) To Cure a Weakling Child

07) Goon Gumpas

08) Yellow Calx

09) Girl/Boy Song

10) Logan Rock Witch

01) 4

02) Cornish Acid

03) Peek 824545201

04) Fingerbib

05) Carn Marth

06) To Cure a Weakling Child

07) Goon Gumpas

08) Yellow Calx

09) Girl/Boy Song

10) Logan Rock Witch

3:37

2:14

3:05

3:48

2:33

4:03

2:02

3:04

4:52

3:33

Data Complete 80%

Total Rating

Total Rating

![]() (1 users)

(1 users)

Back Cover

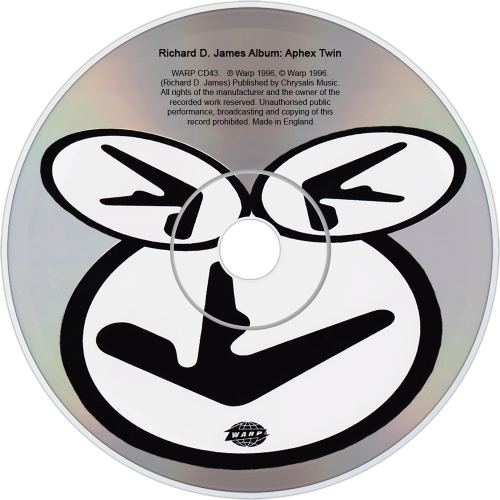

CD Art

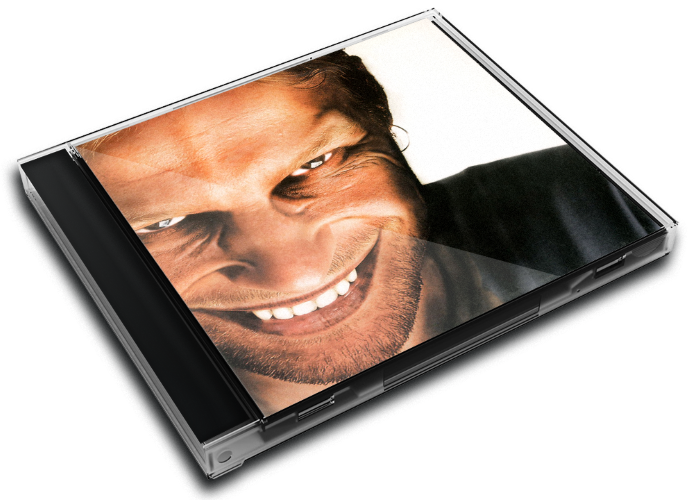

3D Case

3D Thumb

3D Flat

3D Face

3D Spine

First Released

![]() 1996

1996

![]() Electronic

Electronic

![]() Hypnotic

Hypnotic

![]() Electronic

Electronic

![]() ---

---

![]() Medium

Medium

![]() Album

Album

![]() 0 copies

0 copies

Album Description

Available in:

Richard D. James Album is an electronic album by Aphex Twin, whose real name is Richard David James. It was released on Warp Records in 1996. The work features use of software synthesizers and unusual beats. It is his fourth official full-length album. The album garnered high acclaim from music critics, and was named 40th in Pitchfork Media's "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s" list. It was also placed #55 on NME's Top 100 Albums of All Time in 2003.

User Album Review

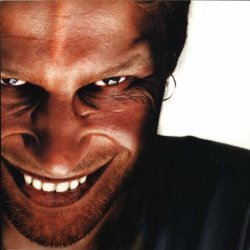

On 1977's spooky "Hall of Mirrors," legendary German electro-pioneers Kraftwerk sang a line that underscored the hyperreal appeal of the clean-cut, automaton-like likenesses that made up their album portraits and public image: "He fell in love with the image of himself/ And suddenly the picture was distorted." But decades later, it's hard not to hear the line as a prophecy for the brain-bending work of Richard D. James, known to most music fans as Aphex Twin, who shares with his progenitors a taste for altering his visage in the service of his shapeshifting music. But where Kraftwerk seemed to jokingly transcending their humanity, James and his collaborator Johnny Clayton took an opposite tact, deconstructing images of the producer to look more and more fallibly human. It was move that, at the time, felt representative of the compositions he was churning out, works that similarly seemed to toy with the uncanny valley between man and machine.

Years before his face was superimposed onto terrifying children or bikini-clad co-eds, James' craggiest features came to the forefront on the painting covering his 1995 album ...I Care Because You Do, and even more menacingly in the high-contrast photo that appeared on the cover of 1996 follow-up Richard D. James Album, which presented the artist's mug against a blinding white background. His smile is more sinister, his crow's feet more shadowy, his pores more gaping. In 1996, Aphex Twin was at height of his fringe-mainstream notoriety, and the Richard D. James album cover was the first impression that many had of him as a person; it seemed to reveal the freakish prankster in all his creepy potential, his grin more Cheshire Cat than villainous hedge fund founder.

Sometime after James released 1992's Selected Ambient Works 85-92 and 1994's Selected Ambient Works Vol. II, two albums of ambient ethereality he claimed were inspired by lucid dreaming, the man decided he wanted to make mischief. Not to gush, but it's completely insane that Selected Ambient Works Vol. II, ...I Care Because You Do, and Richard D. James Album were released one year apart, in 1994, 1995, and 1996, respectively. Either of the bookending two would be career-defining on their own, yet they're by the same person, with the transitional Do bridging works so totally disparate that it ends up sounding like neither of them. Richard D. James Album emerges from this shockingly quick progression as a whole new Aphex Twin, replete with concrete melodies and jumpy song structures, lifting away the distant fog of his ambient material completely.

Despite his prolific release schedule, the man had barely hinted at this direction before. With no track titles and not much discernible rhythm, Selected Ambient Works Vol. II. was all harrowing, gorgeous texture. (The poppier first volume was quietly legendary, but James wasn't exactly known as a melodist.) The various acid-synth excursions and rave-rattlers he'd released under various aliases up until that point (AFX, Polygon Window, Caustic Window) didn't feature any kind of easy calling card other than the prolificacy of the Aphex brand on the sleeve and its growing legend status. ...I Care Because You Do had beats, but they were all over the place; the maddening "Wax the Nip" felt like the drums were out of sync with the tune itself, and "Ventolin" verged on unlistenability with its high-pitched squeals, which seemed to mimic those one would presumably hear while overdosing on the titular albuterol inhalant. He was learning to make mischief, and it was all a bit of a mess.

So the most shocking thing about Richard D. James Album arriving only a year later is not its ballyhooed swan dive into jungle and drill'n'bass, but rather its neatness. Its knotty, gnarled intestines are all safely tucked in; there isn't a second of the record that feels out of place, and every stray surprise serves a comedic or melodic function—like the the sudden, stammering human voices that interrupt "4" a couple times, or the galloping pile of percussion that repeatedly sneaks up on you on "To Cure a Weakling Child." The mix is vivacious and sparkling, full of chutes and ladders and baroque oboes and pizzicatos alongside fart jokes. Parts of it bring to mind a mobile hanging above a crib ("Logon Rock Witch"), and others evoke the constructive joy of opening a new Lego set ("Carn Marth").

If all this sounds rather juvenile, that's because it is. In 1996, the year of the album's release, James said in an interview that the album was a tribute to his dead brother (Richard is the Aphex Twin, get it?). If the man who previously claimed to own a tank and subsequently lived in a bank is to be believed, that brother was stillborn, three years before James' mother successfully conceived him and gave him the same name. By way of proof, the cover of the Girl/Boy EP released shortly before Richard D. James Album featured a gravestone that supposedly belonged to James' late brother (the photo was also included in booklet for the American edition of the full-length). Because the name "Richard James" is fairly common, and Aphex Twin has been known for straight-up lying to reporters for much of his career, there are plenty of reasons to be skeptical of this narrative. But what a hook: it lends gravitas to the fact that Richard D. James Album was quite possibly the first electronic album of the post-rave era to be about something.

Whether or not you trust the veracity of the memorial photo, there's no doubt that Richard D. James Album, with its toy-like sounds and lullaby-esque melodies, was exploring childhood nostalgia sonically—in the way, say, Michel Gondry has onscreen, in DIY fantasias like The Science of Sleep. And the narrative backstory is a killer entryway to its zany hyperactivity. Anyway, kids make up a lot of lies. The auteur had a firm grip on the boyhood feel and packaging that he juxtaposed against some the most beautiful and uptempo music of his career, which is ultimately what backs up all of this horsemeat.

The inaugural tune "4," very well may be Aphex Twin's greatest song, and one of the greatest opening bids in all of music history. It's essentially a chamber-pop instrumental, with a cutesy synth darting through pensive strings waylaid over a burbling, stop-start drum pattern. It has parts resembling verse and chorus, and grows more intense as it tumbles through each, before the song glitches and a person quietly clears their throat, only for the song to start back up again. This happens three or four times the exact same way, suggesting that the song goes on into infinity, which is an important number to a kid. "4" is both beautiful and full of wonder, tightly conceived and exceedingly open-ended—and –hearted.

The more playful breakbeats of "Cornish Acid" follow, and "Peek 824545201" zips and thwips, stringing together Autechre-like bubbles of alien percussion beneath another calming melody line on some kind of low-end, ghostly bass organ. "Fingerbib," a woozy synth ballad takes over, building and cresting over a skeletal rhythm track. These are the strongest melodies of James' career, and the first time he ever conceived such rich compositions. Supposedly this album took him longer to make than anything he'd done previously, and the amount of care he's put into it shows. Even the doodles, like the post-classical "Goon Gumpas," have a discernable tug of heartbreak.

Then there's the debut of James' vocals. On "To Cure a Weakling Child," he alters himself to sound like (of course) a child, surrounded by what sounds like an array of cut-up tongue clicks. On "Milkman," the verse is a suspiciously banal invocation of the titular character ("I wish the milkman would deliver my milk in the morning") that sets up a naughty chorus ("I would like some milk from the milkman's wife's tits"). And the American version of the record includes the Girl/Boy EP, which means it ends with him crooning, "I am always throwing up / Vegetables with cheese, if you please."

Humor had always been present in Aphex Twin's music, visuals, and mythology, but never so blatantly before. If the framing device of a tribute to an imaginary infant made this synthesis possible, then so be it. But on this album he hits upon a devilish peace of mind—a collision of chaotic-melodic impulses that he would continue to channel for another few years and releases—before having kids of his own, long after.

Where his previous works trafficked in impressionism, this was the first time he seemed to be projecting a persona. The human-like qualities of the sounds in this new palette were strong enough to support, not just impressions, but audible emotions—wringing warmth from a hyper-mathematical often criticized as cold. There's an earnest, feigned innocence to Richard D. James Album, achieving a balance between the music-box prettiness of classical music repackaged for children and still-innovative rhythms that crashed into walls like test dummies. It's one of his least perverse records in the aural fact, with shorter tunelets and clearly marked paths, with a cap on pain and noise for the sake of it. It may have presaged the distorted, Marilyn Manson-influenced body horror on 1997's occasionally industrial Come to Daddy, but beyond their drum'n'bass leanings, all the two share is a pockmarked humanity.

Richard D. James Album is one of the most thoroughly realized electronic albums ever made; listening to it in 2016, it seems not just ahead of its time, but ahead of a more colorful and polyrhythmic era we're either still waiting on or unable to conjure up in our collective post-pubescent mind. It makes you realize that the scary-looking James on the cover is not a villain but a friendly monster, like the inhabitants of Where the Wild Things Are. If electronic music has matured in the last 20 years, Richard D. James Album is a childhood snapshot of the wild imagination we all outgrow. All that lingers is that stupid grin.

SOURCE: https://thump.vice.com/en_uk/article/vvnx4j/aphex-twin-richard-d-james-album-20-years

External Album Reviews

None...

User Comments

Available in:

Richard D. James Album is an electronic album by Aphex Twin, whose real name is Richard David James. It was released on Warp Records in 1996. The work features use of software synthesizers and unusual beats. It is his fourth official full-length album. The album garnered high acclaim from music critics, and was named 40th in Pitchfork Media's "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s" list. It was also placed #55 on NME's Top 100 Albums of All Time in 2003.

User Album Review

On 1977's spooky "Hall of Mirrors," legendary German electro-pioneers Kraftwerk sang a line that underscored the hyperreal appeal of the clean-cut, automaton-like likenesses that made up their album portraits and public image: "He fell in love with the image of himself/ And suddenly the picture was distorted." But decades later, it's hard not to hear the line as a prophecy for the brain-bending work of Richard D. James, known to most music fans as Aphex Twin, who shares with his progenitors a taste for altering his visage in the service of his shapeshifting music. But where Kraftwerk seemed to jokingly transcending their humanity, James and his collaborator Johnny Clayton took an opposite tact, deconstructing images of the producer to look more and more fallibly human. It was move that, at the time, felt representative of the compositions he was churning out, works that similarly seemed to toy with the uncanny valley between man and machine.

Years before his face was superimposed onto terrifying children or bikini-clad co-eds, James' craggiest features came to the forefront on the painting covering his 1995 album ...I Care Because You Do, and even more menacingly in the high-contrast photo that appeared on the cover of 1996 follow-up Richard D. James Album, which presented the artist's mug against a blinding white background. His smile is more sinister, his crow's feet more shadowy, his pores more gaping. In 1996, Aphex Twin was at height of his fringe-mainstream notoriety, and the Richard D. James album cover was the first impression that many had of him as a person; it seemed to reveal the freakish prankster in all his creepy potential, his grin more Cheshire Cat than villainous hedge fund founder.

Sometime after James released 1992's Selected Ambient Works 85-92 and 1994's Selected Ambient Works Vol. II, two albums of ambient ethereality he claimed were inspired by lucid dreaming, the man decided he wanted to make mischief. Not to gush, but it's completely insane that Selected Ambient Works Vol. II, ...I Care Because You Do, and Richard D. James Album were released one year apart, in 1994, 1995, and 1996, respectively. Either of the bookending two would be career-defining on their own, yet they're by the same person, with the transitional Do bridging works so totally disparate that it ends up sounding like neither of them. Richard D. James Album emerges from this shockingly quick progression as a whole new Aphex Twin, replete with concrete melodies and jumpy song structures, lifting away the distant fog of his ambient material completely.

Despite his prolific release schedule, the man had barely hinted at this direction before. With no track titles and not much discernible rhythm, Selected Ambient Works Vol. II. was all harrowing, gorgeous texture. (The poppier first volume was quietly legendary, but James wasn't exactly known as a melodist.) The various acid-synth excursions and rave-rattlers he'd released under various aliases up until that point (AFX, Polygon Window, Caustic Window) didn't feature any kind of easy calling card other than the prolificacy of the Aphex brand on the sleeve and its growing legend status. ...I Care Because You Do had beats, but they were all over the place; the maddening "Wax the Nip" felt like the drums were out of sync with the tune itself, and "Ventolin" verged on unlistenability with its high-pitched squeals, which seemed to mimic those one would presumably hear while overdosing on the titular albuterol inhalant. He was learning to make mischief, and it was all a bit of a mess.

So the most shocking thing about Richard D. James Album arriving only a year later is not its ballyhooed swan dive into jungle and drill'n'bass, but rather its neatness. Its knotty, gnarled intestines are all safely tucked in; there isn't a second of the record that feels out of place, and every stray surprise serves a comedic or melodic function—like the the sudden, stammering human voices that interrupt "4" a couple times, or the galloping pile of percussion that repeatedly sneaks up on you on "To Cure a Weakling Child." The mix is vivacious and sparkling, full of chutes and ladders and baroque oboes and pizzicatos alongside fart jokes. Parts of it bring to mind a mobile hanging above a crib ("Logon Rock Witch"), and others evoke the constructive joy of opening a new Lego set ("Carn Marth").

If all this sounds rather juvenile, that's because it is. In 1996, the year of the album's release, James said in an interview that the album was a tribute to his dead brother (Richard is the Aphex Twin, get it?). If the man who previously claimed to own a tank and subsequently lived in a bank is to be believed, that brother was stillborn, three years before James' mother successfully conceived him and gave him the same name. By way of proof, the cover of the Girl/Boy EP released shortly before Richard D. James Album featured a gravestone that supposedly belonged to James' late brother (the photo was also included in booklet for the American edition of the full-length). Because the name "Richard James" is fairly common, and Aphex Twin has been known for straight-up lying to reporters for much of his career, there are plenty of reasons to be skeptical of this narrative. But what a hook: it lends gravitas to the fact that Richard D. James Album was quite possibly the first electronic album of the post-rave era to be about something.

Whether or not you trust the veracity of the memorial photo, there's no doubt that Richard D. James Album, with its toy-like sounds and lullaby-esque melodies, was exploring childhood nostalgia sonically—in the way, say, Michel Gondry has onscreen, in DIY fantasias like The Science of Sleep. And the narrative backstory is a killer entryway to its zany hyperactivity. Anyway, kids make up a lot of lies. The auteur had a firm grip on the boyhood feel and packaging that he juxtaposed against some the most beautiful and uptempo music of his career, which is ultimately what backs up all of this horsemeat.

The inaugural tune "4," very well may be Aphex Twin's greatest song, and one of the greatest opening bids in all of music history. It's essentially a chamber-pop instrumental, with a cutesy synth darting through pensive strings waylaid over a burbling, stop-start drum pattern. It has parts resembling verse and chorus, and grows more intense as it tumbles through each, before the song glitches and a person quietly clears their throat, only for the song to start back up again. This happens three or four times the exact same way, suggesting that the song goes on into infinity, which is an important number to a kid. "4" is both beautiful and full of wonder, tightly conceived and exceedingly open-ended—and –hearted.

The more playful breakbeats of "Cornish Acid" follow, and "Peek 824545201" zips and thwips, stringing together Autechre-like bubbles of alien percussion beneath another calming melody line on some kind of low-end, ghostly bass organ. "Fingerbib," a woozy synth ballad takes over, building and cresting over a skeletal rhythm track. These are the strongest melodies of James' career, and the first time he ever conceived such rich compositions. Supposedly this album took him longer to make than anything he'd done previously, and the amount of care he's put into it shows. Even the doodles, like the post-classical "Goon Gumpas," have a discernable tug of heartbreak.

Then there's the debut of James' vocals. On "To Cure a Weakling Child," he alters himself to sound like (of course) a child, surrounded by what sounds like an array of cut-up tongue clicks. On "Milkman," the verse is a suspiciously banal invocation of the titular character ("I wish the milkman would deliver my milk in the morning") that sets up a naughty chorus ("I would like some milk from the milkman's wife's tits"). And the American version of the record includes the Girl/Boy EP, which means it ends with him crooning, "I am always throwing up / Vegetables with cheese, if you please."

Humor had always been present in Aphex Twin's music, visuals, and mythology, but never so blatantly before. If the framing device of a tribute to an imaginary infant made this synthesis possible, then so be it. But on this album he hits upon a devilish peace of mind—a collision of chaotic-melodic impulses that he would continue to channel for another few years and releases—before having kids of his own, long after.

Where his previous works trafficked in impressionism, this was the first time he seemed to be projecting a persona. The human-like qualities of the sounds in this new palette were strong enough to support, not just impressions, but audible emotions—wringing warmth from a hyper-mathematical often criticized as cold. There's an earnest, feigned innocence to Richard D. James Album, achieving a balance between the music-box prettiness of classical music repackaged for children and still-innovative rhythms that crashed into walls like test dummies. It's one of his least perverse records in the aural fact, with shorter tunelets and clearly marked paths, with a cap on pain and noise for the sake of it. It may have presaged the distorted, Marilyn Manson-influenced body horror on 1997's occasionally industrial Come to Daddy, but beyond their drum'n'bass leanings, all the two share is a pockmarked humanity.

Richard D. James Album is one of the most thoroughly realized electronic albums ever made; listening to it in 2016, it seems not just ahead of its time, but ahead of a more colorful and polyrhythmic era we're either still waiting on or unable to conjure up in our collective post-pubescent mind. It makes you realize that the scary-looking James on the cover is not a villain but a friendly monster, like the inhabitants of Where the Wild Things Are. If electronic music has matured in the last 20 years, Richard D. James Album is a childhood snapshot of the wild imagination we all outgrow. All that lingers is that stupid grin.

SOURCE: https://thump.vice.com/en_uk/article/vvnx4j/aphex-twin-richard-d-james-album-20-years

External Album Reviews

None...

User Comments

No comments yet...