Members

1 Male

1 Male

Origin

American

American

Genre

Jazz

Jazz

Style

---

Mood

---

Born

Origin

Genre

Style

---

Mood

---

Born

![]() 1962

1962

Active![]() 1962 to Present...

1962 to Present...

Cutout![]()

Alternate Name

Art Farmer Quartet

4 users

4 users

4 users

4 users

4 users

Artist Biography

Available in:

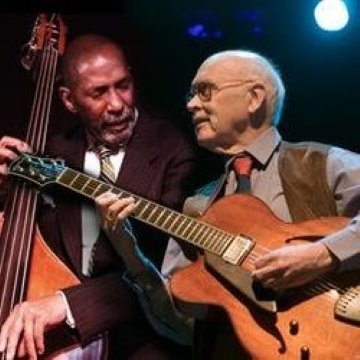

History : Art Farmer and Jim Hall joined forces in late 1962, each was an established jazz soloist. Farmer, born in Council Bluffs, Iowa and raised in Phoenix, made his professional debut in Los Angeles in 1945. By the end of the fifties, he had amassed an impressive discography, including recordings with Wardell Gray, Lionel Hampton, Clifford Brown, Quincy Jones, Gigi Gryce, Sonny Clark, Horace Silver and Gerry Mulligan. From 1960-62, Farmer co-led the acclaimed Jazztet with Benny Golson. Hall, born in Buffalo, New York, and raised in Cleveland, also worked in LA as a member of the Chico Hamilton Quintet and later, in two editions of the Jimmy Giuffre 3. Hall bounced between LA and New York through the end of the 50s, recording with John Lewis, Ben Webster, Paul Desmond and Zoot Sims, in between gigs with Giuffre. After an international tour with Ella Fitzgerald, Hall settled in New York, and became one of the city’s top-call session men, adding recordings with Gerry Mulligan, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Sonny Rollins and Bill Evans to his already burgeoning discography.

Hall had worked with Rollins since the tenor saxophonist had returned to the jazz scene in 1961. Although Hall was very complimentary towardsRollins as a band leader, he was planning to leave the band around the end of 1962. The Farmer/Golson Jazztet would disband around that same time, but a few months earlier, they played a New York nightclub opposite Rollins. The two men met and decided to form a quartet. Although the actual date of their meeting is not known, it may have been around August 1962, when Hall played in the rhythm section for the album, “Listen to Art Farmer and the Orchestra”.

Farmer and Hall began assembling their quartet in late 1962 or early 1963. Farmer said in an interview that the quartet did not need a pianist, because Hall could cover the chords and provide linear counterpoint on guitar. Farmer and Hall sought rhythm players that could freely interact with the front line. Steve Swallow became the group’s permanent bassist shortly before the group began recording in July 1963, but there were at least two bassists before him. Hall stated in an interview that Ron Carter was the quartet’s bassist until he was hired away by Miles Davis (Carter first recorded with Miles on “Seven Steps to Heaven”, recorded in LA on April 16). Bob Cunningham, who had played with Dizzy Gillespie, Steve Lacy and Ken McIntyre, played bass on the first known recording of the Farmer/Hall quartet. According to Gene Lees, Walter Perkins had been the drummer from early in the quartet’s existence; there is no record of any drummer holding the chair before him. One important instrumental change came from the leader. Farmer had doubled on flugelhorn for a year or so, but made the larger horn his primary instrument right before starting the quartet with Hall. In the liner notes to the quartet’s first album, Lees wrote that once Farmer made the change, he would only play his trumpet when practicing at home.

In their early months, the quartet played several times at the Half Note in New York. This would become their home base, and would be the setting for one of the quartet’s finest recordings. Swallow also played frequently at the Half Note before joining the group (usually with Al Cohn and Zoot Sims), and Farmer first heard Swallow play in that context. After Farmer hired him, Swallow hosted several quartet rehearsals at his apartment in preparation for their first album. However, separate rehearsals became a rarity after that, as the group preferred to develop their arrangements on the bandstand. With the quartet playing five sets of music per night, and touring frequently, they developed a quick and easy rapport.

The quartet’s repertoire was chosen for its melodic content. Farmer brought in most of the tunes, emphasizing rarely-heard standards, but Hall was the de facto musical director of the group, creating most of the arrangements and lead sheets. Hall may have been responsible for the quartet’s recording contract with Atlantic Records, since the guitarist was a longtime friend of John Lewis, who was both the musical director of the Modern Jazz Quartet and an established Atlantic artist. With several progressive albums by John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman in the Atlantic catalog, plus the MJQ producing well-received albums, the company seemed keen on recording cutting-edge instrumental jazz. The Farmer/Hall quartet fit right in to this agenda.

It might be a surprise to today’s audience that nearly half of the quartet’s recordings came from television appearances. As was stated many times during this period, jazz and television shared the quality of immediacy. While most TV shows at the time were presented on videotape, many of the aesthetics of live television were still in place, and presenting jazz on the small screen required little editing or post-production. In the US, the Farmer/Hall quartet appeared on NET, the predecessor to PBS, while their UK performance was broadcast on BBC. Because both of these networks were non-commercial, the group was allowed to play extended performances without being interrupted for advertisements.

The first recording of the Farmer/Hall quartet comes from an appearance at the New School in New York. The first half of the concert included a talk on jazz by composer Hall Overton and was broadcast on WNET-TV. No video of the program is known to exist, but an audio recording of the final minutes of the broadcast has survived and is available for listening on the web. Overton drones on for three pedantic minutes before turning the focus to the quartet, who then performs “Stompin’ at the Savoy”. After Hall’s oblique reading of the melody, Cunningham walks and then bows through his two-chorus solo. The rhythm section continues through Perkins’ drum solo where he adjusts the drum pitch by pressing his elbow on the drum head. We can clearly hear Perkins scatting the rhythms as he solos. When Farmer enters, Hall’s accompaniment is already reduced from what he had played during the drum solo. Eventually all of the background disappears as Farmer plays unaccompanied (but still on the changes) for a full chorus. The band returns under Farmer, but the performance ends abruptly with a station announcement for the following week’s program (there may not have been commercials, but there were time limits!). According to John S. Wilson’s report in the New York Times, Farmer promised—and delivered—a full set by the quartet after the broadcast ended. About a month later, Wilson reviewed the Newport Jazz Festival, where Farmer and Hall appeared with the Gerry Mulligan Sextet. At one point, Mulligan and the other members of the band left the stage while Farmer and Hall played a duet. No recording of this impromptu performance has been found, but it may exist in the Voice of America holdings at the Library of Congress.

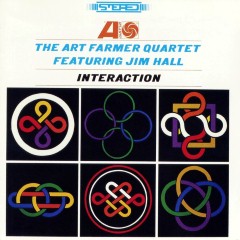

On July 25, 1963, the quartet entered the Atlantic studios in New York for the first of three sessions that would produce the album “Interaction”. On the first track, the then-new “Days of Wine and Roses”, Farmer opens by playing the tune in E-flat with Swallow providing a few telling musical comments. For the solos, the band modulates into F, and then goes back to E-flat for the final theme statement. In between, there are lyric solos by Farmer, Hall and Swallow, and a brilliant unaccompanied full-chorus duet by Farmer and Hall where the two lines intersect, diverge and stretch the harmony. Hall was well-known for his progressive harmonic thinking, but it’s clear that Farmer’s ears were growing in this direction, too, and his solos with Hall are among the most adventurous he ever played. The opening chorus of “By Myself” displays an interesting idea that Farmer would use throughout these recordings: he plays a deliberately wrong note in a strategic place to imply advanced harmonies. Here, it is the last note of the first A section, and Farmer plays it down a half-step. And just to show that it wasn’t a mistake, he plays it exactly the same way in the closing chorus. Farmer and Hall make the most of the recurring pedal point in their solos, and when Swallow’s turn comes, his solo is framed with a loose interplay by the other three members of the quartet. Swallow’s work on acoustic bass may be quite a revelation for those who only know him as an electric bassist. His sound is quite full and he displays great agility on the instrument. Due to his advanced technique and great musical imagination, he was able to act as a third melodic voice in the quartet.

The next session, on July 29, yielded only one tune for the album, a samba version of Charlie Parker’s “My Little Suede Shoes”. This was a feature for Walter Perkins, and the track opens with a dialogue between drums and flugelhorn. Hall plays a brilliantly conceived solo based on a handful of small motives. Farmer’s solo also starts with short, seemingly disconnected ideas, but after connecting the thoughts, he closes with long flowing lines over straight-ahead 4/4 time. Perkins’ solo starts with the combination of scat and elbow-adjusted drum, but then he moves to his crash cymbal, and while holding the cymbal tightly between his forearm and his chest, he bends the cymbal while striking it with a mallet to create an unusual choked sound (On the “Jazz Casual” television show, we can see Perkins demonstrate the technique).

Jazz critic Martin Williams was present for the final session on August 1, and he provides us with the only description of “Great Day”, a spiritual-like piece written by Tom McIntosh. The group made several attempts at recording this work, and while there were complete takes available to the producers, the song was left off of the original album. Apparently, Perkins wanted to accompany part of the arrangement on tambourine (and had practiced his technique during the previous week), but Farmer asked for the part to played on the drum set. MacIntosh admitted that the song needed work, and Williams reported that a two-bar break was deleted and later re-inserted into the arrangement. At least one take had a flawed ending, and it sounds like the group was struggling to find a suitable groove. Fortunately, the quartet was able to move on from this point, and record all of the cuts for the second side of the album. A stunningly beautiful version of “Embraceable You” was apparently the finest of several attempted takes. Farmer is the principal soloist and his lines are distinctive for both their grace and their harmonic adventurousness. In the last chorus, Hall and Swallow delicately move back and forth across the line of accompaniment and dialogue. A light-touched “Loads of Love” opens with an extended duet for Farmer and Perkins (on brushes). As on the broadcast of “Savoy”, Farmer’s solo is based on the unheard chords, and he skillfully outlines the changes as he goes. Perkins solos on his own before Swallow enters with a dramatic quadruple-stop. Bass and drums continue in duet for a while longer before Hall makes his first entrance on the track—nearly three minutes in! There’s delightful interplay by the rhythm section before Farmer re-enters, hinting here and there at the melody. The album concludes with the premiere recording of Sergio Mihanovich’s lyric waltz, “Sometime Ago”. Hall had heard the song during a trip to Buenos Aires, and his solo on the present version brings out the harmonic tension from deep within the composition. Swallow’s deep-toned solo features passionate lyric lines, and Farmer waltzes through the changes while Hall and Swallow offer animated commentary.

Wide Thumb

Clearart

Fanart

Banner

User Comments

No comments yet..

No comments yet..

30%

30%